8 - Proxy politics, part 3: Turkey and the Nile River Basin

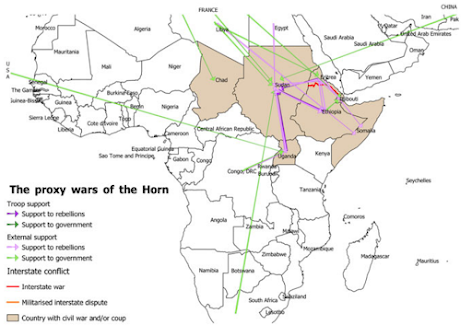

Hi everyone and welcome back to my blog! This will be my last entry on proxy politics and it will discuss Turkey's involvement in the Nile River Basin. It will also be my last entry on this blog. Turkey, the Middle East, and the Nile River Basin (Google Maps) Turkey’s involvement is much more recent than that of the Gulf countries, but it is nonetheless important. The Turkish government started the ‘African expansion’ in 2003, a strategy aiming to develop economic and strategic relations with African countries, and the country is now a major investor in Ethiopia and Sudan ( Cascao et al. 2019 ). Ankara also used to have a good relationship with Cairo. However, the former’s support of Mohamed Morsi (from the Muslim Brotherhood) after the Egyptian revolution of January 2011 became a source of conflict after the coup in 2013. It led to damaged diplomatic relationships and interrupted economic investment with the majority of the USD 5 billion...