7 - Proxy politics, part 2: The Gulf countries and the Nile River Basin

Hi everyone and welcome back to my blog! This entry will explore the proxy relationships between the Middle East and the Nile River Basin.

Those two regions have been interacting for a long time now. Due to their proximity and common religious and cultural background, the Middle East and the Nile River Basin relationships can be traced back far in the past (Cascao et al. 2019). However, I am interested in the more recent interactions. Those relationships now have a proxy nature and are impacting the Nile Hydropolitical Security Complex (Idem).

The involvement of Gulf countries

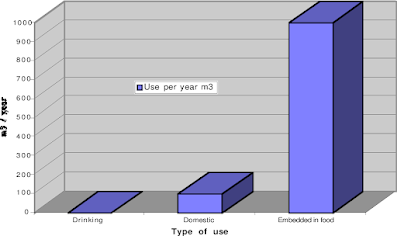

Countries of the Gulf (Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar) have to deal with a water-scarce environment. Growing food is therefore an issue. A useful but invisible and silent process that they have been using is virtual water (Allan 1997). Importing food reduces the amount of water used. With the objective of minimising their food imports, the Gulf countries started heavily investing in agriculture abroad, especially in the Nile River Basin (Cascao et al. 2019). That region (Sudan and Ethiopia) is favoured, not only for its access to water, but also for its geographical and cultural proximity, as well as for the ‘political advantages’ it provides (Sandstrom et al. 2016).

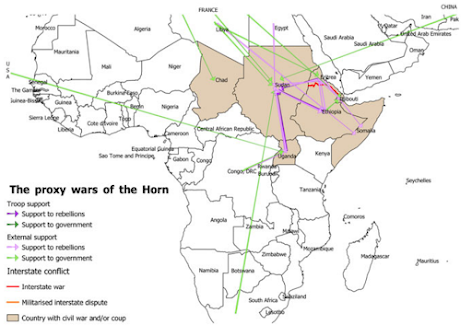

Sudan’s arable land has a potential of 105 million hectares of which only 18 are used (Cascao et al. 2019). That makes Sudan an ideal investment opportunity for the Gulf countries interested in agriculture. Saudi Arabia funded 3 dams in exchange for being able to cultivate 1 million hectares of land near them (Idem). Qatar has invested over USD 1.5 billion in different sectors, including agriculture (Idem). Moreover, it provides ‘political advantages’. First, the opportunity to fight against Iran’s growing influence, which is seen as a threat by the Gulf countries. Second, for Saudi Arabia, the opportunity to put pressure on Egypt during the occasional disagreements.

In the case of Ethiopia, the cultural, social and religious bonds are weaker than in Sudan. However, economic cooperation has surged in the last decade. Saudi Arabia invested over USD 3 billion in 2017, which made it part of the four biggest investors in the country. It is also the main destination for exportation (Cascao et al 2019). Qatar also has agreements in place with Ethiopia. Those relationships are also part of a larger chess game. It enables the Gulf countries to extend their influence and to control the migration routes. It is also ‘intimately linked to the Saudi/ Gulf enduring power play with Egypt’ (Cacao et al. 2019, 220). Therefore, the Nile is used as a ‘card’ to implement their agenda in occasional disputes with Egypt (Idem).

This involvement in the Nile River Basin is not free of implications for the Nile Hydropolitical Security Complex. The investments in Sudan led the country to increase its water use, thus decreasing the water flow to Egypt. It also affects the hydropolitics dynamics by increasing Ethiopia and Sudan’s bargaining power over Egypt in a context of GERD negotiations (Cascao et al. 2019).

Comments

Post a Comment