5 - The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, part 3: pathways towards cooperation

Hi everyone and welcome to my last entry on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) in which I will discuss pathways and challenges to cooperation.

In 1999, the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) was created. Its aim is to foster cooperation among riparian countries by being a forum for discussion and collaboration (NBI). The organisation seeks sustainable win-win scenarios for all countries (NBI). However, because of the NBI’s favourable position on the GERD, Egypt froze its membership in 2010 (Ghanem 2017). This decision rendered any NBI projects or discussions about the GERD obsolete (Tawfik 2016a). As long as Cairo takes no part in the initiative, cooperation between Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia on the matter of the dam must come from another organisation.

After talks between the three governments in Khartoum in 2015, the Declaration of Principles (DoP) was signed. For the first time, they saw eye to eye on several aspects of the GERD’s management. Cairo, Khartoum and Addis Ababa agreed to (Horn Affairs 2015):

use studies from experts to plan the filling of the reservoir

implement a coordination mechanism with dams downstream

give Sudan and Egypt the chance to buy electricity first and cheaper

follow principles of ‘equitable and reasonable utilisation’ and ‘causing no significant harm’.

Although the DoP provides a pathway towards cooperation, there are still many grey areas. Indeed, Ethiopia kept its right to unilaterally manage the dam in cases of ‘urgent circumstances’ (Tawfik 2016b). This might cause disputes in the future. Moreover, the DoP left ‘opened the door for different interpretations and expectations’ (Idem, 1046). Also, the DoP did not address some of the most polemical topics such as the period of filling, how it will affect Egypt’s historical share of water, or what significant harm means (Idem). Therefore, there is still a long way to go before cooperation can be reached but the DoP might be a start.

I believe that the concept of benefit sharing is what could really make a difference. This concept implies that sharing the water is not the only solution: one could also share the benefits derived from cooperation (Sadoff and Grey 2002). Indeed, there are four kinds of benefits possible. First, there are ‘benefits to the river’. It touches on the improved water quality, protected biodiversity and habitats (Idem). Second is ‘benefits from the river’. This has to do with the economic benefits derived from the river (Idem). Third, there are benefits from the ‘reduction of costs because of the river’ which can include non-cooperation costs (Idem). Fourth is ‘benefits beyond the river’ (Idem). This one focuses on cooperation in other fields (trade, hydropower, etc…).

A benefit sharing model can be achieved by highlighting the benefits for all actors and by sharing costs. In the case of the GERD, as I have explored in the last two posts, the benefits are plentiful but so are the costs. Therefore, potential mitigation policies could include an enhanced water management from Egypt. Using the High Aswan Dam to mitigate potential water shortages, switching national agriculture to water-efficient crops, and increasing groundwater withdrawals could help (Heggy et al 2021). Ethiopia could compensate Egypt by leasing (at low cost) some of its surplus agricultural lands (Idem). Offering subsidized electricity could compensate for the losses incurred by the filling of the GERD’s reservoir on the High Aswan Dam’s electricity production (Idem). However, such a method would require agreeing on the size of the financial damages, which is unlikely (Idem).

Even putting the decades of mistrust between Egypt and Ethiopia aside, there are still many challenges to implementing a benefit sharing model (Tawfik 2016b). First, both governments made the topic of the GERD extremely politically sensitive, which does not prepare the public for any concessions (Tawfik 2016a). Second, there are too many institutions involved in the dispute without any coordination between them (Idem). Third, there is no platform for negotiation as Egypt is no longer part of the NBI. Finally, with Ethiopia and Sudan increasingly needing water and Egypt not willing to decrease its share, there are conflicting trends in water uses (Idem).

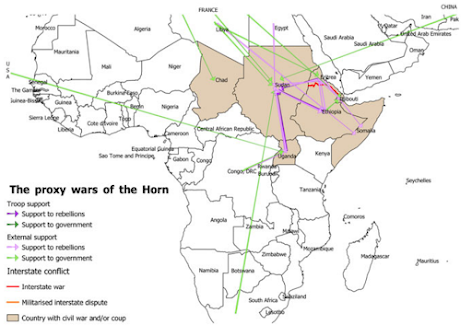

In conclusion, the GERD comes with plenty of benefits and costs which could be mitigated by a benefit sharing approach, enabled by using the NBI as a platform and following the DoP. However, the many challenges in the way makes it highly difficult. Moreover, with the filling of the GERD having started, tensions are high and a drought period could turn out to be very dangerous for the stability of the region already torn in disputes.

It will be interesting to see if the NBI improves as a platform for negotiation in the future, especially as Ethiopia begins filling the GERD, with impacts felt by downstream riparians. Do you see Egypt ever returning to the NBI?

ReplyDelete