4 - The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, part 2: Egypt and Sudan's position

Hi and welcome back to my blog! This is the second entry on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and I will focus on how Egypt and Sudan feel about the project.

Satellite view of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (Wikipedia)

Egypt is mainly afraid of the decrease of the amount of water available to them in the filing period of the reservoir. Indeed, the country is highly dependent on the Nile water as 90% of its water comes from the river (Jabeer 2020). Any amount of water diverted would harm Egypt, especially during droughts. If the filing occurs in dry years, it will significantly hurt their water supplies and the electricity generated by the High Aswan Dam (Zhang et al. 2015). However, it is in Ethiopia’s sake to fill the reservoir as fast as possible, because ‘any delay in the export of power and the realisation of expected revenues would be extremely costly’ (MIT, 2014, p. 8). Egypt is thus strongly opposed to this project and demands that the filing period be as extended as possible.

Another reason why Egypt is so hostile to the GERD is geopolitical. As I discussed in the previous blog post, by building and filing this dam, Ethiopia challenges Egypt’s hydro-hegemony over the Nile. Being so dependent on Ethiopia would leave them vulnerable. Moreover, Cairo perceives the size of the reservoir as a sign that Adds Ababa wishes to control the Nile (Tawfiq 2016). They fear Ethiopia’s vision of the Nile riparian countries. It aims to have them specialised in specific areas: industry and services for Egypt, hydropower for Ethiopia, and agriculture for Sudan (Arsano 2007). Although this would indeed reduce Egypt’s need for Nile water (agriculture uses 85% of the water reserves), it is not what Egypt wishes as one third of its citizens are employed in the agricultural sector (NBI 2012). For Cairo, fighting the GERD is therefore fighting Ethiopia’s geopolitical growing threat and vision.

Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopian dam talks in 2018 (Scribd)

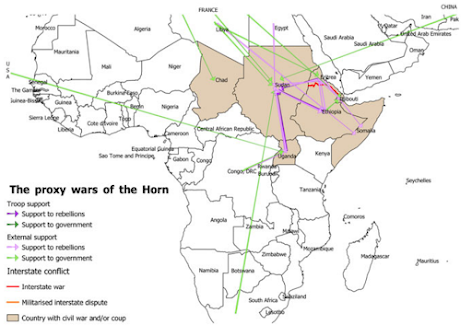

And they do so in different ways: by trying to block international funding (Abul Gheit, 2014, pp. 249–262; Abu Zeid, 2015), or by seeking new alliances. In 2014, Egypt and South Sudan formed a new alliance in the form of a military agreement (Aman 2014). This move aimed to isolate Ethiopia and pressure its government into making concessions (Gomaa 2021). Ethiopia did not idly stand by: in the same year, Addis Ababa and Khartoum joined forces and created a joint military force (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Sudan, 2014a). However, since then and as a result to the unilateral filing of the reservoir, Sudan switched back to being an Egyptian ally: in April 2021, both countries organised a joint military exercise (Sabry 2021). But this does not leave Ethiopia diplomatically isolated as the government is backed by the remaining of the Nile riparian countries in the Cooperative Framework Agreement (NBI).

Sudan sees this dam as an opportunity. Indeed, Sudan’s agriculture is often harmed by floods from the Nile which the GERD would prevent (Tawfiq 2016). It would also reduce the amount of sedimentation in the river and would therefore increase Sudanese dams’ electric production by 35% once the GERD will be in operation (Tawfiq 2016). Moreover, the dam would also be a source of cheap electricity (Tawfiq 2016). Therefore, Sudan switched from being a historical Egyptian ally to endorsing the Ethiopian project in 2014 (Tawfiq 2016).

However, since Addis Ababa unilaterally started filling up the GERD’s massive reservoir of 74 billion cubic meters in 2020, Sudan changed its stance and is now opposed to the filling of the reservoir as long as an agreement is not reached (Sabry 2021). In fact, as a reaction to the second filling of the GERD reservoir in July 2021, the Sudanese government called on the UN security council to act (Dabanga 2021).

In 2013, the former Egyptian president declared that ‘if the Nile water diminishes by one drop, then our blood is the alternative’ (BBC 2013). This statement resonates with my second entry in this blog about (the absence of) ‘water wars’. Indeed, since then, there has been no armed conflict or declaration of war despite the high animosity between the two countries. Nevertheless, as I argued, it is crucial not to underestimate the potential for water conflict in the future simply because there have been so few in the past. I will thus discuss pathways for peaceful resolution of this dispute in a third blog post about the GERD.

Comments

Post a Comment