3 - The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, part 1: Why does Ethiopia need this dam?

Hi everyone and welcome back to my blog! This entry is going to be about a very complex and conflictual topic: the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). It will be the first of the three posts I will write about the GERD. It will focus on what exactly is the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, and what it could bring to Ethiopia.

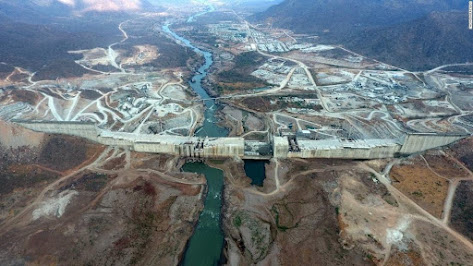

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam is located in the North of Ethiopia, close to the border with Sudan, on the Blue Nile. This section of the Nile meets with the White Nile in Khartoum and supplies roughly 80% of the Nile water (Wikipedia). Ethiopia unilaterally started the construction of the dam in 2011. The project is older but the required capacities (political, diplomatic, institutional, technical, and economic) were lacking (Arsano 2007). It is the largest dam ever constructed on the Blue Nile. It’s hydroelectric power generates around 16,000 GW/year, which is enough to provide electricity to Ethiopia’s 109 million inhabitants (International Panel of Experts Report 2013). In fact, Ethiopia would be left with so much surplus that the GERD could potentially provide for 234 million people, which is predicted to be Ethiopia’s population in 2060 (worldpopulationreview.com).

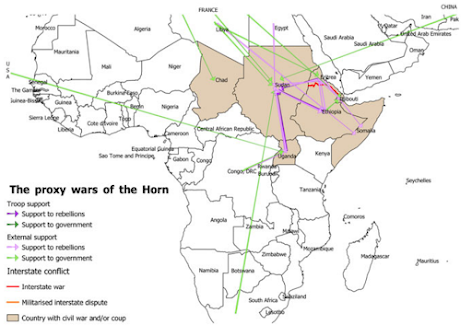

In the meantime, this electric surplus will be used for trade. It could be sold to Egypt, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, and Djibouti and make Ethiopia ‘Africa’s energy hub’ (Tawfik 2016a). On top of contributing to the development of surrounding countries, Addis Ababa could profit massively from this surplus. And that is not the only advantage to Ethiopia. Another economic benefit is job creation: 15,000 Ethiopians are currently working on the project, and ‘future opportunities will be created when business facilities are established at the site of the project’ (Tawfik 2016b). Moreover, according to the Rocky Mountain Institute, electrifying small rural farms, thus making them more efficient, could result in 4 billion dollars in economic opportunities, which represents 5% of the country’s GDP.

It is also important to note that this $4.8 billion project has been largely self-funded (Veilleux 2013). It is the citizens of Ethiopia who, through taxes and investments, financed the GERD. As a result, the dam can act as a source of massive national pride, and a unifying topic in a country torn apart by the Tigray war. The GERD would also address Ethiopia’s exposure to climate variability (Block & Strzepek 2011). This vulnerability has a high burden on the country’s development. The World Bank (2006) estimated that one third of Ethiopia’s growth potential is lost to hydrological variability.

Finally, this predicted economic growth and most of all control of the Blue Nile water flow upstream would place Ethiopia as a major geopolitical actor where Egypt used to be the sole one along the Nile. In fact, Tawfik even considers the dam as a ‘game changer’ (Tawfik 2016b). Indeed, it challenges Egypt’s ‘hydro-hegemony’ (Zeitoun and Warner 2006). This concept refers to the position of power over the other riparian states. Hydro-hegemony can be achieved through utilitarian, normative and legal, or ideological tactics (Zeitoun & Warner, 2006). In the case of Egypt, it has been done through more or less legal tactics. In 1929 and 1959, Egypt signed treaties guaranteeing that they would have control of 66% of the Nile river flow, and that they would have a say on any project upstream that could harm their access to water (Mbaku 2020). Ethiopia was not involved in both of those agreements. Using Cairo’s political instability, Addis Ababa emerged as a counter-hegemonic actor (Tawfik 2016b). Through protests in international forums against the treaties, alliances, the development of domestic expertise, the discourse of ‘equitable utilisation’ of water, Ethiopia worked on a ‘veiled contest’ of Egypt despite their ‘apparent consent’ (Cascao 2008). This era of ‘apparent consent’ is now over and their contest is not veiled anymore (Tawfik 2016b). This project is a ‘revolution’ in the ‘hydropolitical stalemate’ that is the Nile (Verhoeven 2011).

And this is partly why Egypt is strongly opposed to the GERD, a position which I will explore in the next blog post. Thank you for reading!

Comments

Post a Comment